We know that women with sickle cell disease suffer milder symptoms than men, so could this difference hold the key to developing more effective treatments?

Researchers at King’s College London think so. Working in tandem with Muhimbili University in Tanzania, they analysed the differences between male and female patients’ haemoglobin, the red pigment in red blood cells that transports oxygen around the body.

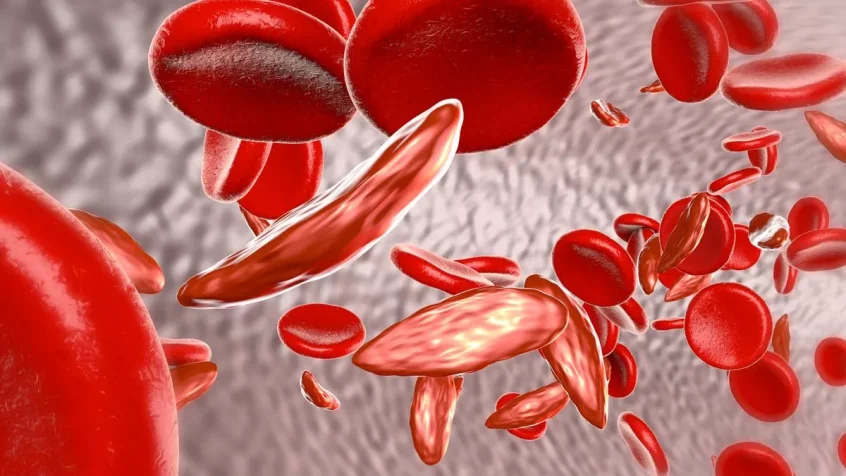

Sickle cell disease is the name given to a group of diseases where red blood cells are rigid and abnormally shaped. This is due to the cells containing an abnormal version of haemoglobin.

As a result of their shape and rigidity, they have a shorter lifespan and are more likely to block blood vessels, causing damage and inflammation.

One feature of sickle cell disease is that people have milder symptoms when they have more F-cells – a type of red blood cell containing immature foetal haemoglobin.

During the stage when the foetus is developing, it’s common for red blood cells to have this version of haemoglobin but it’s mostly gone by adulthood. However, some people with sickle cell disease have higher than average levels of F-cells, and these survive longer in the bloodstream than the sickled versions of red blood cells.

It seems the female biological sex promotes a higher level of F-cells in the blood. Researchers compared F-cell production and changes in their numbers between female and male sickle cell disease patients and found there were significantly higher levels of F-cells in the women.

Another interesting observation was made when researchers were studying immature F-cells in bone marrow which is where red blood cells are formed. More of them were found in female bone marrow than male.

This suggests the reason for the higher level of F-cells between women and men is two-fold – more of them are produced in the female bone marrow, and such cells also have a better survival rate when circulating in the female bloodstream.

From this knowledge, the researchers conclude that new therapies should aim to stimulate the development of foetal haemoglobin within patients themselves.

They hope understanding the causes behind the differences between the sexes will help the development of these drugs.

This promising work could only happen when international collaborators work closely together as UK researchers have with their counterparts in Tanzania. Distances and cultures should be no impediment.