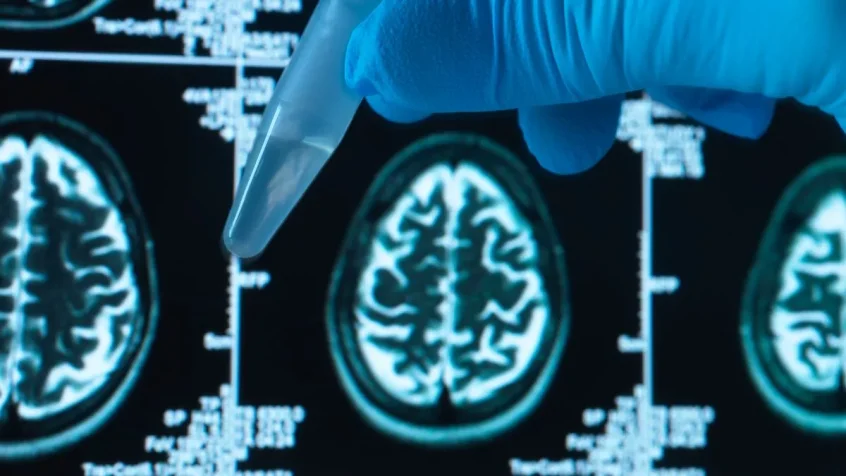

With Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s we often refer to the brain cells “communicating” with each other through connections, and how that communication ceases when those connections are destroyed.

But what if they actually “talked” to one another? Researchers claim that listening to the “conversations” of brain cells could provide clues to the early causes of Parkinson’s disease.

Parkinson’s is the second most common neurodegenerative condition after Alzheimer’s and the fastest-growing neurological disease in the world. In Wales, there are relatively more sufferers than anywhere else in the UK.

The brain becomes progressively damaged over many years, but the early stages remain a mystery with much of the damage happening before symptoms appear.

Now a team at Cardiff University is using cutting-edge techniques to help understand its onset. By taking cells “back in time”, the researchers are hoping for new treatments.

“The journey of Parkinson’s, we think, is quite a long one,” said Dr Dayne Beccano-Kelly, who leads the research. “We might see symptoms at later stages of life, on average at around 65 years old… but we know cells in the brain are very important for movement and cognition, and stop working at much earlier ages.

“We also see about a 60-80% loss by the time people come into clinic, but we know that doesn’t happen overnight. So there’s a window of time before cells begin to die in which we may be able to help.”

The researchers are doing mind-bogglingly clever stuff, collecting skin cell samples from those with Parkinson’s and without. The team then “reverse-age” those cells – driving them back in time so they revert to stem cells. They then encourage these to develop into neurons – brain cells.

At various stages, the team tries to tap into the electrical communication happening between the cells using hi-tech equipment.

“The idea is we’re trying to listen in to the cross talk or the communication between neurons… a bit like a secret agent listening in to a conversation between two people,” Dr Beccano-Kelly said.

By looking at the differences that occur over time in Parkinson’s cells versus non-Parkinson’s cells, the team hopes to get a handle on factors that contribute to the condition, such as brain cells being unable to clean up waste proteins inside them, leading to cell death.

Professor Julie Williams, director of the UK Dementia Research Institute in Cardiff, said the research was “pushing the boundaries”.

“By understanding the mechanisms we can test for novel drugs – drugs that are out there used for other purposes – which could come into the clinic quickly.”