A friend of mine came home from the US having had a – faecal transplant – which was something of a conversation stopper when talking about her trip.

Apparently they’re quite well accepted Stateside, especially in complementary medical circles. She’d had one for a serious infection while in hospital for a gallbladder operation.

I’ve written about these faecal transplantations (FMTs) before because as we learn more about the importance of our gut bacteria, the microbiome, we realise we can treat seemingly unconnected conditions by manipulating it.

How does FMT work? Well, doctors collect faeces from a healthy donor and then “transplant” them into the rectum of the patient.

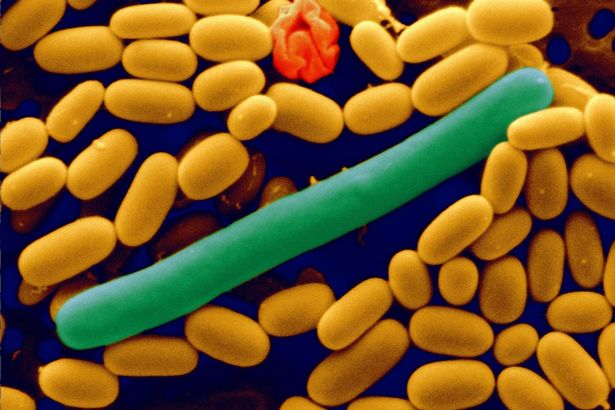

The first, and so far most effective, use of FMT has been to treat a condition where the gut is overwhelmed by an infection with the bacterium Clostridium difficile, or C.diff. It often results in a lengthy stay in hospital with severe diarrhoea, fever and abdominal pain, sometimes lasting for months, if not years. And it’s not uncommon, affecting more than 14,000 people every year and killing more than 1,600.

We all carry C.diff but it’s kept in check by the good bacteria in your bowel. If, however, your good bacteria fall in number, by say a course of antibiotics, C.diff can thrive. And it’s tenacious. Little can touch it. But repopulating the gut with healthy bacteria is an option.

These come from someone else’s gut. In other words, a faecal transplant.

It can be done via a tube passed through the nose into the stomach, but we’ve found there’s a higher success rate if it is done via the rectum, and it takes only minutes. It’s 90% effective in people with C.diff that’s resisted every other treatment.

And believe it or not, there are “super donors”, people whose transplants are particularly effective.

What makes them special? Well, according to a Kiwi researcher Dr Justin O’Sullivan, their stools tend to have high levels of “keystone species”, bacteria and viruses that work together to form chemicals which help fight a particular disease, be it Type 2 diabetes or Crohn’s disease.

Dr O’Sullivan thinks that identifying the right super donors for particular medical conditions would be a huge step forward, not just in treating gut diseases, but also possibly conditions we know are linked to an abnormal microbiome such as Alzheimer’s, multiple sclerosis and asthma.

We’re a long way off having FMT on the NHS but with one in 10 patients who get C.diff dying, maybe we shouldn’t be.